I came across Dr Bill Rogers‘ work on behaviour management early in my career.

I started working in some really tough schools. In some ways, it was lucky, because it made the rest of my career less challenging and prepared me for my very first principal’s role in 1995 (teaching principal), at a school with a teacher turnover rate of 400% over the two years prior to my starting.

A lot of my success with challenging classes was due to the work of behaviour management guru Dr Bill Rogers – a real teacher with extensive expertise in behaviour management.

Bill’s advice cover’s everything from preventative behaviour management techniques, to consequences and one-on-one programs with particularly disruptive students. I like all of Bill’s work and recommend it to all of you. However, it was his work on positive correction that impressed me most because it filled a void not covered by many other approaches.

Positive correction refers to the on-the-spot techniques you use to manage students while teaching. It assumes you have already established things such as rules, routines and relationships with your students. However, you use it before having to use formal consequences (or in some school’s – being sent to the Responsible Thinking Classroom). In short, it is a set of strategies that help you nip small problems in the bud and keep everyone’s focus on the lesson at hand.

Here are my favourite five on-the-spot strategies for nipping small problems in the bud.

Bill Rogers Strategy #1 Direction With Tactical Pausing

Giving a direction involves stating what you want the student/s to do. Examples of directions could include statements such as, face this way and listening please … Troy, working silently please … Sam, pop that in the bin thanks. Pretty simple really. There are only three tricks to doing it well.

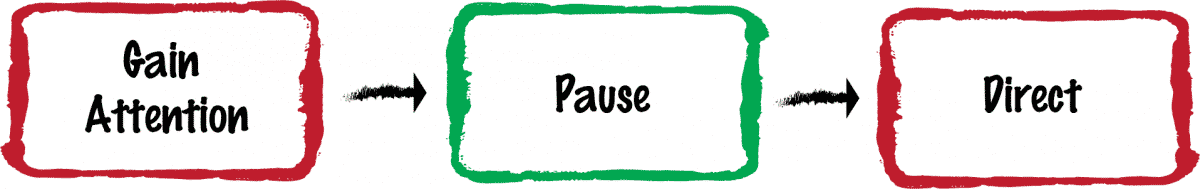

You gain their attention by stating their name, pausing, and then giving the direction once they are looking at you. For example: Tony (pause) lining up sensibly please. When directing a whole class you could say: Everybody, everybody (pause) looking at me and ready to start thanks. The pause is critical, but often overlooked. Without the pause, you are halfway through your direction (or more) before the student even catches on that you are talking to them.

The second trick is to focus on what you want the students to do, not what you want them to stop doing. There are times when you can’t do this, but most of the time you can. For example, it’s better to say working silently than it is to say stop talking.

Finally, you need to speak calmly and confidently. Remember, the whole point of your direction is to correct the behaviour with minimal disruption to the lesson. Yelling at a student won’t achieve this, and nor will speaking in a timid or pleading voice.

Strategy #2 No Why Questions

This strategy by Bill Rogers is even easier. Don’t ask questions such as Why are you doing that? Or, Why would you do that? These sorts of questions invite long-winded, irrelevant answers. Remember, your goal is to stop the misbehaviour and quickly move on with the lesson.

If you do ask a question, it is much better to use ones that focus directly on the behaviour:

Imagine a student hasn’t got all the stuff he needs for class. It is easier, quicker and less disruptive to ask him if he needs to borrow a pen and a textbook than it is to delve into why he wasn’t prepared. Remember, I’m only talking about on-the-spot reactions. You may need to delve deeper with a student who frequently doesn’t have his stuff – but not ‘on-the-spot’, during a lesson.

Bill Rogers Strategy #3 Blocking With Partial Agreement

Some teachers struggle with this one, but it is one of the most potent behaviour management techniques you could use.

It involves blocking secondary arguments and focusing exclusively on what you want the student to do.

Imagine that a pair of students were talking to each other when they should have been working silently. You direct them to work in silence, but they respond with a whining complaint, but we’re not the only ones talking. You refuse to enter the side argument, restate your direction and move away.

Partial agreement is one (particularly useful) way to block tangent-arguments from taking over. It involves using two words to sidestep the tangent – maybe and but. In the above example where two boys fire back that they weren’t the only ones talking you reply by stating … MAYBE you aren’t … BUT I need you two to work silently.

Strategy #4 Conditional Permission

There is a time and place for everything, and Bill Rogers recommends that you use conditional permission to reinforce this.

The when-then structure offers you an easy way to use conditional permission. When you have finished your notes, then you can search for suitable images for your assignment. When you have eaten your fruit, then you may go to play.

You can also use the yes-when structure to answer students as they ask for permission. Yes, we can have the air-conditioner on, when it’s hotter than 24°C.

There are other words that you can use (e.g. after-then), but the principle remains the same.

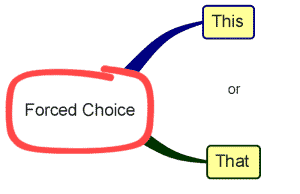

Bill Rogers’ Strategy #5 Forced Choices

Students choose how they behave. The forced-choice technique is a way of highlighting this while clarifying what the choices are. You often use it after, or in combination with other strategies.

For example, you may direct Sarah to work silently. Soon after, she starts chatting again. You then force her choice by something like, Sarah, you can choose to work silently, or I will have to move you.

Tony provides another opportunity to force a choice when he is playing with his music player in the class. You can force the choice by saying something such as, Tony, you can put that away or on my desk – you choose.

Sometimes, choices may be more serious. Shenae, you can choose not to wear makeup again, or I will call your parents.

There are various ways you can force a choice, but the keyword is always or.

Forced choices work well, but only if you consistently follow through when needed. When forcing a choice:

My Favourite 5 Strategies In A Nutshell

To recap, my 5 favourite Bill Rogers’ strategies for dealing with misbehaviour on-the-spot are:

- Gain attention, pause and then give a direction

- Don’t ask ‘why questions‘ – when dealing with small misbehaviours

- Use partial agreement (maybe-but) to stop conversations going off on a tangent

- Use conditional permission (when-then) when students ask to do something

- Give students a forced choice when a direction has been ignored