Checking for understanding is an essential aspect of teaching. You need to check that your students have understood what you taught them. It’s how you know what to do next.

However, if you are like most teachers, your time is already stretched thin, and you don’t want to be creating even more mountains of marking to take home with you every night.

The good news is that you don’t have to. Checking for understanding can occur within the flow of your day-to-day lessons. The key, according to Dylan Wiliam, is in learning to listen.

What Do You Listen for When Checking for Understanding?

1) Do They Get It?

You listen to see if your students ‘get it’, whatever ‘it’ might be in a lesson. This requires you to be very clear about what ‘it’ is that you want them to learn.

For example, you may want your students to be able to describe the energy transfer and transformation involved in simple scenarios. These scenarios could include dropping a ball or releasing a mousetrap.

2) Misconceptions

However, you also listen to the thinking behind your students’ responses. This may highlight any misconceptions that they hold. And, identifying misconceptions is part of checking for understanding.

In the above example, you would listen for common misconceptions such as:

5 Ways to Quickly Check for Understanding

All these systems involve asking your students some form of a multiple-choice question.

Multiple-choice questions do have some inherent limitations. However, if constructed thoughtfully, they are an ideal way to check your students’ understanding at the end of a lesson.

Crafting Thoughtful Multiple-Choice Questions

The first step involves considering what it was that you wanted your students to learn.

Let’s continue with our example of transferring and transforming energy. You could state that when you hit a golf ball, energy is transformed from the club to the ball. Then have your students indicate true or false using the thumb’s response. This question determines whether students understand the difference between transferred and transformed.

Alternatively, you could present your students with a short series of true-false statements:

You could also include a question designed to warn you about student misconceptions. For example:

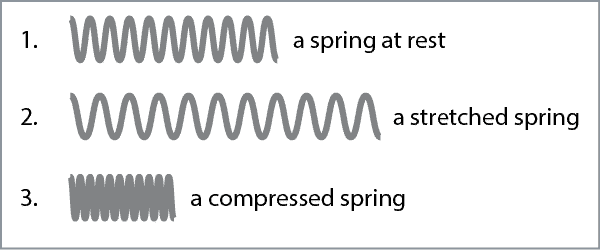

In the above diagram, which spring has potential energy? The:

- Spring at rest

- Stretched spring

- Compressed spring

The correct answer is 2 & 3. Obviously, you need to get your students used to the idea that there will sometimes be more than one right answer. Assuming you have already done this, the question helps to raise flags about a common misconception. This misconception is that only stretched objects have elastic potential energy.

You could present all these questions in just a few minutes, and with nothing more than your students’ fingers, you have found out enough about their understanding to make a sound decision about what to do next.